THE LAST TRIBES OF BORNEO

In production

documentary 52 minutes. 2023/2024

Introduction

Indigenous people possess a profound relationship with their natural landscapes and depend on these territories for their cultural, religious, health, economic needs, and ultimately their survival. Their deep knowledge of natural systems and the care they take in the utilization of resources can and has provided critical insight for building a sustainable future. Sadly, in most instances, their voices and practices have been ignored. This willful disregard of native voices over centuries has placed humanity in peril.

The relationship between the indigenous communities (the Dayaks and the Punans) of Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo and the forest is the subject of this

52′ documentary.

The Dayaks and the Punan tribes

The Dayaks and the Punans have inhabited the island of Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) for thousands of years. It is a vast area rich in natural resources and of great diversity.

But it continues to experience large-scale devastation due to industrialization and deforestation. To make matters worse, the effects of climate change are steadily compounding problems in the region. While the Indonesian government has preserved 45 percent of Borneo as conservation areas and forests, many other areas have been transformed into palm oil plantations, or scraped clean to extract coal, oil, and gold.

In 2022, I documented the impacts of various industries (national and foreign) on the Dayak people, who live in the forests of the interior of the island mostly in the upper Mahakam river region.

In 2023, I went to scout locations in the north and east kalimantan among the Punan Malinau and Punan Batu tribes.

https://patrickmorell.com/works/environment/#punan

Today, several Dayak organizations and NGO’s such as AMAN and WALHI are waging an arduous fight against this encroachment of various industries (Palm oil, mining and logging).

https://patrickmorell.com/works/people/#landrights

The intent

Indigenous cultures share a collective belief in the power of nature. This invisible force is recognized throughout their world, as well as in names, shadows, all earthly creatures, and in the souls of those who have passed away. The Dayaks call this energy semangat, though virtually every indigenous culture has their own name for it. Because it is invisible it cannot be measured, quantified or monetized. Yet to argue for its non-existence is to proclaim a barren, soulless and even a cynical world that justifies exploitation for no other reason than profit.

Their spiritualized and animistic view of life endows the natural world with meaning and significance and underscores the vital connection indigenous people have to the earth and the cosmos. That is why people and place must be seen as one. They cannot be separated without damage to both. This awareness is clearly lacking in industrialized nations. But however elusive it is to recognize, it is vital to understand because it forms the central belief and obligation from which the proper stewardship of nature’s resources resides. Arguably, the troubles we face today are a direct result of the violation of this sacred reality.

This is why as a filmmaker, it is my belief that this reality must be acknowledged and somehow re-imbued in society for true and effective change to take place.

The latest cognitive studies shows that we are all wired for a belief in something bigger than ourselves.

In my previous films, I have seen how intimate ritualistic events that have been captured on film can move world audiences (including the local audiences where the film was shot) .

My goal was in 2023 (and still is in 2024) to focus on a particular Punan group called the Punan Batu, who live in the upper and remote eastern part of the island.

The only question in this quest was how I could get access to these Punan Batu.

And this is when I heard about the Datuk.

The Datuk

For weeks, I had heard tales of the Datuk (“the Noble Man”) – stories both sinister and intriguing, painting him as a man of influence and power, but also as one shrouded in mystery and controversy. Now, as I prepared to seek his assistance, I couldn’t help but wonder what secrets lay hidden beneath his noble facade.

With determination fueling my steps, I set off into the heart of the forest, to the Bulungan Regency, ready to uncover the truth behind the lies and deception that had brought me to this remote corner of the world.

The mention of the Datuk, a descendant of a long line of sultans who once traded with these tribes, stirred both curiosity and caution within me.

My guide Ester had managed to establish contact with him, and after a brief exchange over the phone, he requested a written note detailing my intentions.

With pen in hand, I poured my heart and soul onto paper, crafting a two-page testament to my earnest desire to learn, to understand, and to share the stories of the Punan Batu with the world. It was a declaration of purpose, a vow to honor the traditions and the dignity of the people whose lives were woven into the fabric of these ancient forests.

As I sealed the envelope containing my note of intention, I felt a sense of anticipation mingled with apprehension.

The journey ahead was fraught with uncertainty, but I was determined to press forward, guided by the flickering flame of hope that burned within me

As we finally reached the Datuk’s house, in Tanjun Selor (Bulungan Regency)

the moment of truth was upon us, and I could only hope that our meeting would mark the beginning of a journey that would shed light on the hidden world of the Punan Batu.

The atmosphere in the Datuk’s living room was warm and welcoming, a stark contrast to the uncertainty that had preceded our arrival.

Despite the language barrier, the conversation flowed smoothly between Ester and the Datuk, with occasional translations allowing me to contribute to the discussion.

It was clear that the Datuk was intrigued by my intentions to document the lives of the Punan Batu in their natural environment and to give them a voice.

I felt a sense of relief wash over me as he expressed his satisfaction with our exchange.

But as with any agreement in these remote corners of the world, there was a price to be paid.

In exchange for his cooperation, the Datuk requested that we provide food and supplies for twenty families in the area, a gesture of goodwill that spoke volumes about the values of reciprocity and community that governed life in these parts.

I eagerly agreed to the terms, grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the betterment of the well-being of the local families and to forge a deeper connection with the community I hoped to film.

It was a rare moment of solidarity in a world too often defined by division and greed, and I savored the feeling of camaraderie that hung in the air.

As the meeting drew to a close, I was introduced to the Datuk’s son, Aldy, a jovial young man whose presence would prove invaluable in the days to come.

With a shared sense of purpose driving us forward, we set out the next day to gather the supplies needed to fulfill our end of the bargain, eager to begin our journey into the heart of the Punan Batu’s forest home.

And so, armed with provisions and a newfound sense of purpose, we embarked on the next chapter of our adventure, ready to immerse ourselves in the world of the Punan Batu and to capture their story for the world to see and hear.

THE PUNAN BATU

The Punan Batu (“Cave Punan”) are the last known mobile hunter-gatherers in Borneo, and probably all of Asia.

Genetic evidence shows that they can trace their roots to the hunter-gatherers of Pleistocene era, which lasted from about 2,5800,00 to 11,7000 years ago.

They arrived in Borneo a few thousands years before the Dayaks prior to the major sea level as the last ice age subsided around 8000 years ago.

In forests along the Sajau River of East Kalimantan, the Punan Batu travel in small groups along a network of caves, rock shelters and forest camps.

Whereas the Dayaks are more sedentary, the Punan Batu are still nomadic.

As hunters and gatherers, the Punan Batu existence is intricately tied to the rhythms of the forest, the forest is not just their home; it’s their entire way of life.

They rely on the forest for everything, from food and shelter to medicine and spiritual connection. Every tree, plant, and animal hold significance in their daily lives, and they possess a deep knowledge of the land and its resources passed down through generations.

The Punan Batu’s diet is simple yet sustainable, consisting primarily of sago tubers supplemented by hunting and gathering.

Sago, extracted from the heart of the sago palm, provides a staple source of carbohydrates, while hunting and gathering provide protein and other essential nutrients.

Extracting starch from the trunks of sago palms may well have formed the basis of pre-agricultural economies of the earliest human immigrants into eastern Indonesia as it has been written by scholars..

When resources dwindle in one area the Punan Batu used move to another, often following the seasons of fruiting trees.

However, as the forest diminishes and game becomes scarcer, the Punan Batu’s traditional diet is under threat.

They face increasing pressure to adapt to a changing environment and find alternative sources of sustenance in the face of dwindling resources.

Asut and his family

The Punan Batu, like many indigenous groups, often follow traditional animistic or indigenous belief systems. These belief systems are deeply connected to nature and spirits associated with their environment. They may not have a single standardized name for their religion, and the practices can vary among different communities. The spiritual beliefs often involve a reverence for nature, ancestors, and spirits that inhabit their surroundings.

The Punan Batu, like many indigenous groups, typically operate without a single centralized leader. Instead, they may have community elders, spiritual leaders, or local representatives who play important roles in decision-making. The leadership structure is often communal and may vary among different communities.

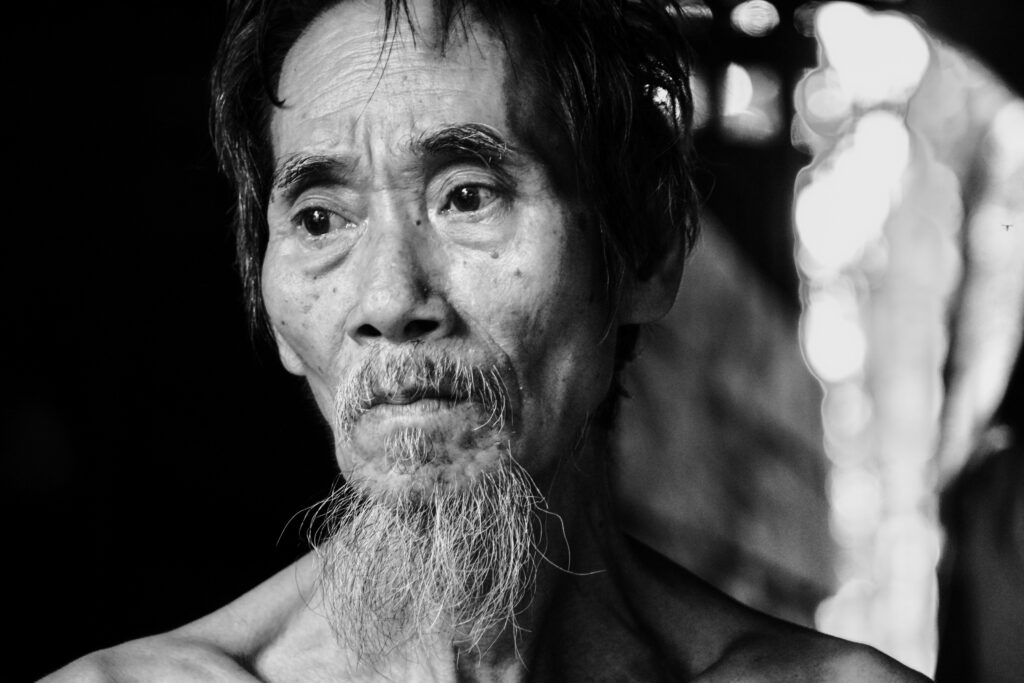

The leader of the clan that I went to discover was Akim Asut. 70 years old.

In the past, the Punan Batu lived in 17 dwellings, but now only 5 of them are filled. Some of them started setting up makeshift huts near the river, which became a source of water and food.

“Now we are starting to find it difficult to hunt. When I was little, it was easy to get game. But now, one or two days it is not certain to get it,” recalled Asut.

Increasingly the difficulty to find food is the main challenge along with the changing land use around them due to mining and clearing of the forest for palm oil plantations.

FOOD

with Akim Asut and his family

Geopark Sajau river

East Kalimantan

October 2023

translated by Fauzan Permana Noor

4K

Reel Duration: 7′ 46″

The Benau forest.

The Benau Forest along the Sajau rive, is a source of livelihood for the Punan Batu people to take shelter, find food, and at the same time preserve traditions.

It has become a preserved area aclled a Geopark thanks partly to the Datuk and his connections in the local government as he was himself a retired civil servant

The total number of these indigenous communities in this area is around 100 people and they still practice a nomadic life, adopt a lifestyle that is in harmony with nature and have a strong dependence on the presence of forests.

Their need for understanding is completely taken from nature.

Asut and his family face significant challenges with the shrinking forest and encroachment of big companies like palm oil plantations and loggers.

Without education and resources, their options may seem limited.

The idea behind the documentary is to explore avenues such as advocacy to raise awareness about their plight, seeking assistance from non-profit organizations or government agencies, or even sustainable livelihood projects that leverage their knowledge of the land while preserving their way of life.

Asut’s role as a mediator could prove crucial in navigating these challenges and finding solutions that benefit his clan and their environment.

MEMORY STICKS

At the opposite of the Dayaks the Punans have little social organization. They live a nomadic lifestyle sleeping in temporary shelters and surviving by trading forest products to settled village.

To communicate with fellow tribesman, they use message sticks attached to trees. A call for aid, for example, is treated with as much urgency as we might use 911. Their communications may also contain warnings about fires, floods, diseases, or other dangers.

Memory sticks

with Akim Asut

Punan Batu

Geopark Sajau river

East Kalimantan

October 2023

translated by Fauzan Permana Noor

4K

Reel Duration: 3′ 50″

Memory sticks

with Akim Asut

Punan Batu

Geopark Sajau river

East Kalimantan

October 2023

translated by Fauzan Permana Noor

4K

Reel Duration: 2′ 20″

The use of memory sticks in the form of small wooden signs with leaves or fibers to guide a tribe toward food or other resources is an intriguing cultural practice.

It seems to be a traditional and ingenious method of communication and navigation within the community.

LATALA

The Punan Batu, like many indigenous communities, often follow indigenous belief systems, animism, or local forms of spirituality. The Indonesian government recognizes various religions, including indigenous beliefs, and individuals may still obtain ID cards without adhering to one of the major organized religions. The government has acknowledged the diversity of religious beliefs within the country.

The Punan Batu’s cultural heritage is reflected in a poetic song-language called Latala which is distinct from the other native languages of Borneo.

Such song languages represent a fluid form of creative expression. Unlike a typical spoken language, where different speakers will identify common objects and concepts using the same words more than 95 percent of the time, there was only a 70 percent overlap in the vocabulary used by different Punan Batu singers, according to a word list Dr. Lansing, an American anthropologue has gathered.

Dr. Lansing has wondered if any unknown words in the songs may have been passed down from Borneo’s Stone Age hunter-gatherers, who we know from bones and cave paintings. Determining whether the Punan Batu are descendants of those cave dwellers, or if they may have coexisted with them, would require a genetic analysis.

LATALA

sung by Bonon, the mother.

Punan Batu

Geopark Sajau river

East Kalimantan

October 2023

4K

Reel Duration: 1′ 39″

LATALA

explained by Asut

Punan Batu

Geopark Sajau river

East Kalimantan

October 2023

4K

Reel Duration: 3′ 23″

“Latala” appears to be a term associated with the Punan Batu, possibly linked to their cultural or spiritual practices. If it’s a song based on signs and codes of conduct, it could be a form of traditional expression that conveys important cultural values, stories, or guidance within the community.

It could also serves various purposes such as transmitting cultural knowledge, preserving traditions, or conveying moral and behavioral guidelines through its lyrics. The use of signs and codes of conduct suggests that it may be a form of communication or expression deeply embedded in the cultural and social fabric of the Punan Batu.

In the song, and according to what they told me the next morning, Bonon, the mother tells me that my arrival must be a good and auspicious sign and that it may prefigure the preservation of their land.

“All what we care about is our forest.” says Asut.

“Please don’t take it from us.”

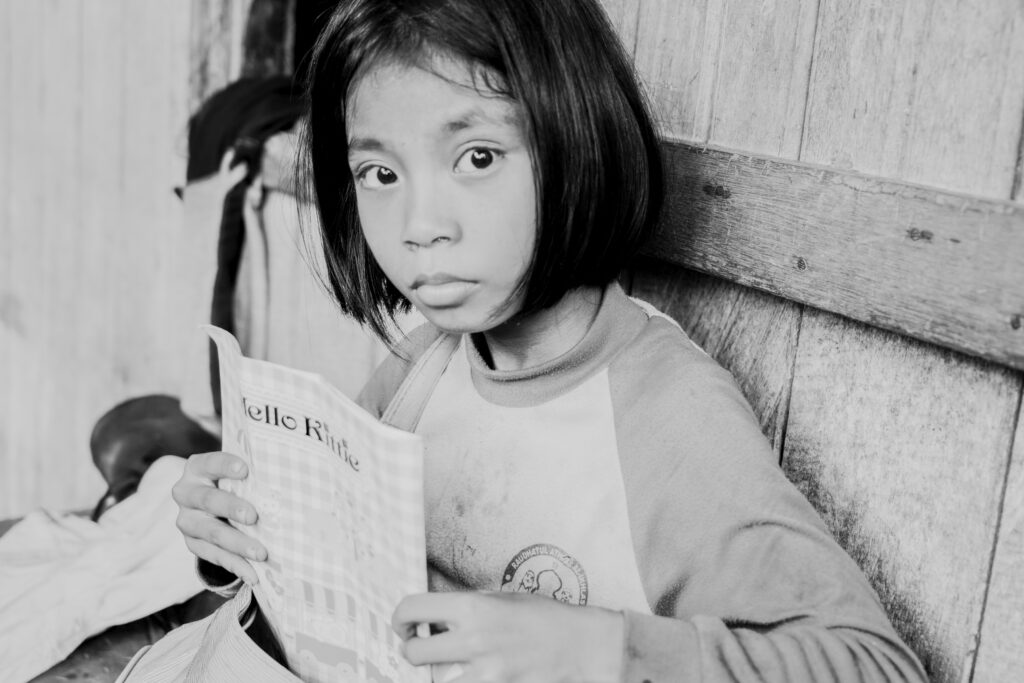

The Children of the Rainforest

Education and Situation: One of the greatest challenges facing the Punan Batu is the lack of access to education. With no schools in their remote villages, children are deprived of the opportunity to learn and grow, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and marginalization.

As outsiders like myself show interest in their culture and plight, the Punan Batu as articulated in the song Latala, see a glimmer of hope and a potential ally in their struggle to preserve their way of life. My presence signifies a chance to amplify their voices and raise awareness about the challenges they face, both locally and globally.

But the question remains: What will the future hold for the Punan Batu?

Faced with the relentless march of progress and the forces of industrialization, they must find a way to adapt while preserving the essence of their culture and identity. It’s a daunting task, but one that they face with resilience and determination, drawing strength from the forest that has sustained them for generations.

THE IMPACT OF INDONESIAN INDUSTRIES

Ironically, as governments around the world seek to reduce their carbon emissions by decreasing their use of high carbon fossil fuels, the clearing of natural forests to make way for palm oil plantations or other industries, represents an enormous source of carbon emissions. Because of weak governance in the forestry and plantation sectors, along with human rights issues that are concomitant, Indonesia risks failing to deliver on its stated public commitment to reduce carbon pollution, while the situation for the Punan grows more precarious.

The Punan’s specialized skills are derived from what is required to live off the land. For countless generations, this has enabled them to survive in a world of unspoiled beauty.

These skills are not easily transferrable to modern life — and that begs the question, why should they be evaluated in that context anyway?

Their technologies have evolved to perfection in the world and the way they live.

Punan people and more particularly the Punan Batu have stood up and protested against the destruction of their lands, but to no avail.

As one Punan told me once , “We are told that it is “state” land. We are not recognized because we do not have an ID card.”

This situation have changed since April 2023 when the tribe has finally gained recognition from the authorities with the delivery of id cards mentioning “traditional belief”

as their “religion” as it is mandatory by the Indonesian authorities.

Recognition through ID cards under the Indonesian constitution implies that the Punan Batu are afforded legal rights and protections similar to other Indonesian citizens. This recognition should grant them access to various services, social welfare, and participation in civic activities.

The Indonesian constitution guarantees equality, and the recognition of indigenous groups’ identities aligns with efforts to uphold diversity and protect the rights of all citizens

Recognition and protection.

Since 2008, the Nature Conservancy (TNC) has helped to design and implement jurisdictional programs in the district of Berau and the province of East Kalimantan.

The region represents a microcosm of Indonesia’s sustainable development challenge to balance the conservation of forests with economic growth while addressing underlying issues of weak land tenure rights, poor land use planning, and widespread granting of concessions that lead to rapid forest destruction.

On April 3rd 2023 a decree was signed by Syarwani the regent of the Bulungan Regency M.Sc, and witnessed by Regional Secretary of Bulungan Risdianto, researcher Mochtar Riady Institute Pradiptajati Kusuma.

This decree gives recognition and protection of the Punan Batu Benau Sajau Customary Law Community (MHA).

This legality is the foundation for their future certainty, both for the living space and culture of the last active hunter-gatherers community in Kalimantan.

https://www.ykan.or.id/en/publications/articles/press-release/kita-jaga-hutannya-kita-jaga-masyarakatnya/