THE MENTAWAIANS

ECHOES of SIBERUT:

The Mentawaian Legacy

Documentary 75'/ 90 mn (TBA)

A Golden Rabbit Films production

In development 2024/ 2025

INTRO: Siberut island:

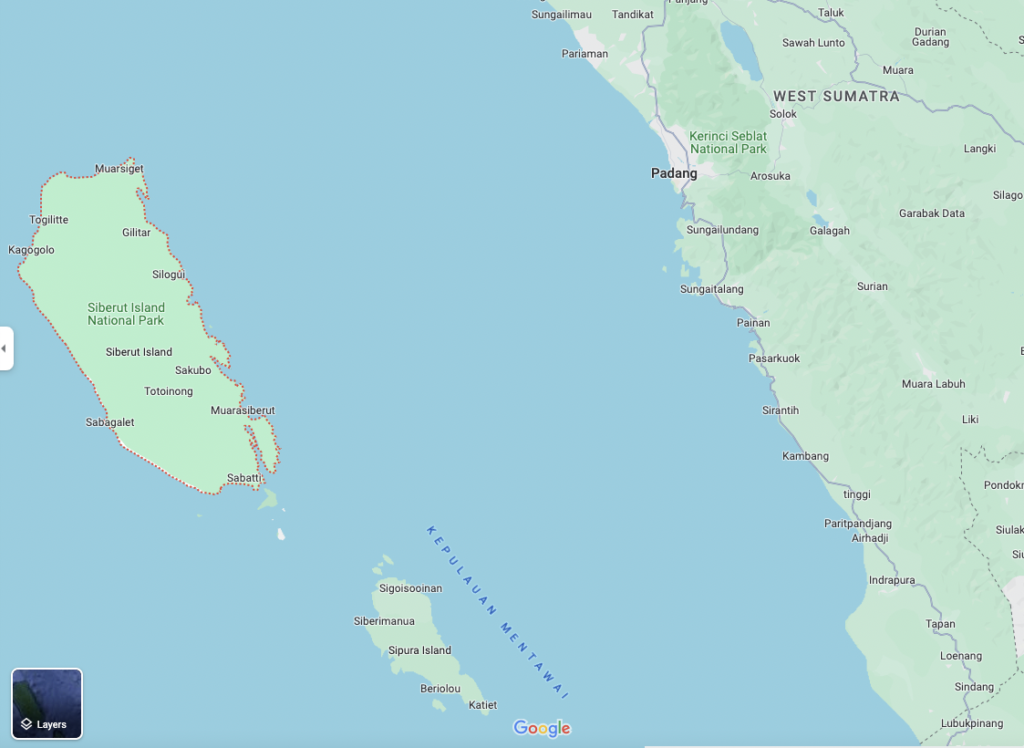

Nestled about 150 kilometers west of Sumatra in the Indian Ocean, the Mentawai archipelago of Indonesia stands distinctly apart from the rest of Southeast Asia.

Its geographical isolation has safeguarded the ancestral culture of the Mentawaian people and preserved relict Indo-Malayan wildlife, while also fostering the evolution of numerous endemic species.

In fact, these islands rank second only to the Galápagos for their astonishing number of unique life forms.

At the heart of this remote island chain lies Siberut—a testament to both the resilience and vulnerability of an ancient way of life.

Here, the Mentawaian people uphold centuries-old traditions, even as modernity and environmental threats steadily encroach upon their land.

“Echoes of Siberut: The Mentawaian Legacy,” delves into the lives of the Mentawaian people, one of Indonesia’s oldest and most enigmatic secluded tribes, whose traditions and daily rhythms are dictated by the lush, unyielded wilderness they call home.

SYNOPSIS:

Living in profound harmony with Siberut’s dense jungle, the Mentawaian people have preserved a semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle that is increasingly rare in the modern world.

They see the soul of the forest in every leaf and stream, a belief rooted in an animistic worldview where every element of nature is imbued with spiritual significance.

This deep connection guides their understanding of the ecosystem, where ancestral spirits are believed to sustain life’s delicate balance.

However, the winds of change are sweeping through Siberut, reflecting broader shifts that have already touched many in the Mentawaian community. While change is a constant, the rapid pace of environmental and societal shifts presents significant challenges.

External influences and the allure of modernity are challenging the tribe’s traditional ways.

Younger generations for example find themselves at a crossroads, eager to explore new opportunities that diverge from the communal ethos of their elders.

Our film explores these tensions, capturing the pivotal moment where tradition meets modernity, and the choices made by the Mentawai could redefine their relationship with the world and each other.

In the same processes threatening biodiversity and ecosystem health also adversely affect indigenous populations. The loss of traditional lands, forest and biomes has profound repercussions on their way of life.|

“Echoes of Siberut: The Mentawaian Legacy” is a poignant narrative about the enduring spirit of the Mentawaian people and their fight to maintain their cultural identity amidst the relentless tide of change.

Science & Exploration amgle

What does the latest research reveal about Siberut’s rainforest biodiversity and its significance to the planet?

Siberut is a biodiversity hotspot with species found nowhere else on Earth. Scientists estimate that over 60% of its flora and fauna are endemic—meaning the island holds biological secrets yet to be fully explored. The Mentawaian’s deep ecological knowledge offers insights into sustainable rainforest living that modern conservationists are only beginning to understand.

Why this story matters?

- Environmental Urgency: Siberut’s rainforest is one of the last untouched ecosystems in Indonesia, but logging and modernization threaten its future.

- Cultural Survival: The Mentawai way of life is disappearing as younger generations migrate to urban centers.

- A Unique Perspective: The film highlights the Mentawaian people’s worldview, featuring exclusive insights from Mentawaian shamans, everyday villagers, hunters, and elders who share their lived experiences and perspectives. Additionally, it includes voices from conservationists and scholars specializing in Mentawaian cosmology and environmental affairs.

- How does indigenous knowledge intersect with modern environmental science?

The Mentawaian people have practiced sustainable forest management for centuries, balancing hunting, foraging, and medicinal plant use.

As modern science catches up, researchers are looking at how their agroforestry practices, traditional medicines, and conservation ethics could inform global sustainability efforts.

- Are there scientists, anthropologists, or ecologists working to document or protect this ecosystem?

Yes. Experts in ethnobotany, anthropology, and conservation have studied the Mentawaians for decades, but their work remains limited.

Deforestation and cultural loss threaten not only the rainforest but also centuries of undocumented knowledge about plant medicine, animal behavior, and ecological balance.

- What happens if Siberut’s rainforest disappears?

Scientists warn that losing Siberut means erasing an entire knowledge system—one that could hold clues for medicine, biodiversity conservation, and climate resilience. The destruction of the rainforest would also accelerate carbon emissions, worsening global climate instability.

The audience

How will viewers feel watching this? What is the emotional takeaway?

They will experience a raw, immersive journey into one of the world’s last truly wild places—where tradition, survival, and nature are inseparable.

The story is urgent, intimate, and visually breathtaking, offering a rare perspective on a culture at a crossroads.

How will the film transport them into the heart of the rainforest and Mentawaian culture?Through unprecedented access and stunning cinematography, viewers will witness the daily lives of the Mentawaian people, from hunting with poison darts to healing rituals led by shamans. The sounds of the jungle, the rhythm of ceremonial songs, and the pulse of the river will pull the audience deep into this untamed world.

Will they witness never-before-seen footage?

Absolutely. The film provides an intimate, rarely captured look at Mentawaian spiritual ceremonies, food rituals, and the delicate balance of life in the rainforest—moments that few outsiders have ever seen.

A call for Action

Beyond the documentary, how can viewers engage?

This is more than just a film—Viewers can engage through:- Supporting indigenous land rights and conservation efforts

- Participating in interactive screenings and discussions

- Accessing educational resources to learn about Mentawaian culture and rainforest preservation

Are there partnerships with conservation initiatives, indigenous advocacy groups, or educational outreach programs?

The project aims to partner with conservation organizations, indigenous rights groups, and academic researchers to ensure that the Mentawai’s story reaches decision-makers and inspires real change.

Why should broadcasters and platforms care?

This story is globally relevant. It connects to climate change, cultural survival, and biodiversity conservation—topics that resonate with audiences worldwide. Whether it’s National Geographic, Netflix, PBS, or an international environmental platform, this film offers a compelling, visually stunning, and socially impactful narrative that will spark conversations and inspire action.

Why Golden Rabbit Films?

- Aligns with Golden Rabbit Films’ mission to showcase powerful stories of environmental and indigenous resilience.

- A visually striking, character-driven narrative that will captivate global audiences.

- Opportunities for festival premieres, streaming platforms, and impact campaigns.

What are we looking for?

- Co-production partnership to help complete post-production and international distribution.

- Broadcast or streaming collaboration for wide audience reach.

- Funding and grants for impact initiatives tied to indigenous land rights and conservation.

Current status

- Part One: Filming and scouting completed. Currently in editing and subtitling.

- Part Two: Environmental topics still to be covered in late summer 2025, along with a few remaining aspects of Mentawaian culture, such as funeral traditions.