THE DAYAKS

People

According to Bernard Sellato, (French anthropologue) “autochthonous people of Borneo (now referred to as Dayak) are believed to have begun arriving from regions further north several millennia ago. These Austronesian’ peoples were of Mongoloid origin and their languages were part of the Western Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family.

They are believed to have brought to Borneo a variety of cultural novelties, including rice agriculture – a date for the earliest known occurrence of rice in Borneo is 2500 B.C.

The name Dayak, generally carrying the meaning of ‘upriver (people)’, is commonly used by outsiders to refer to non-Muslim tribal.”

(SOURCE: © Nordic Institute of Asian Studies 2007)

Dayak – a generic term coined by early Europeans held no significance for the people it described. It is still the catch-all label for any indigenous, non-Malay inhabitants of Borneo.For the most part the Dayaks are not Muslims and live in the interior of the island.

The Dayaks are former head hunters and the original “wild men of Borneo.” They continued to practice headhunting Ngayau, after it was outlawed by the Dutch in the 19th century. Up until World War II most of them were river-dwelling headhunters.

Today, many have been Christianized and forced into settlements. Even though they were the original inhabitants of Borneo they are now greatly outnumbered by Malays and Indonesians.

With the Dayak history of headhunting and animism, few places on earth are as wrapped in such rugged mysticism. Indeed very little has changed in the last century: swidden (slash and burn) farming and ancient customs are still observed and the shaman still holds sway in most villages, despite the presence of mobile phones and satellite TV.

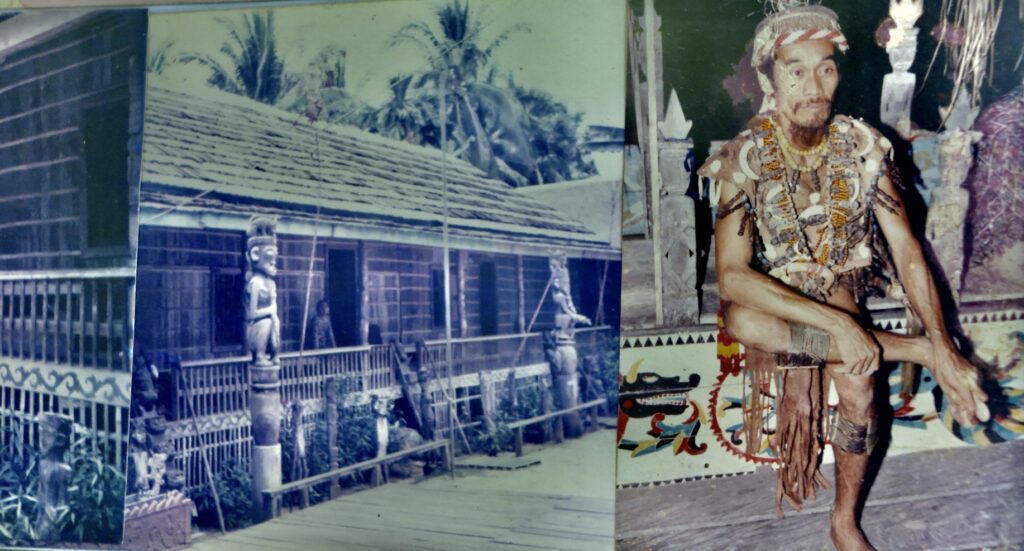

photo by Marc Pinto:

Village guardian sculpture repurposed with framework to hold satellite dish.

Long Bentuk village (formally Long Wei)

East Kalimantan, Borneo.

Courtesy of Mark Johnson.

With over 200 ethnic Dayak groups speaking more than 170 languages and dialects – and spread out over the third-largest island on the planet – the Dayaks are anything but a homogenous crowd.

There are the Kayan – known in Indonesian Kalimantan as Bahau –an important and powerful group cultural group living in the northern and eastern part of the island, the Kenyah and Bidayuh of Malaysian Sarawak and Kalimantan, the Iban (or ‘Sea Dayak’) of Sarawak far up in the north of the island, and the Ngaju of central and southern Kalimantan.

Current estimates put the number of Bornean Dayak people at just over 2 million.

(SOURCE: Mark Johnson. The Kayanic Tradition)

Headhunting

In the past, the highly developed and complex religious practices of the Dayak people involved numerous local spirits and omen animals. Intertribal warfare was common, with headhunting a major feature.

Since the mid-20th century, however, Dayak people have steadily adopted Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism, and Protestantism.

By the early 21st century the vast majority of the population was Christian.

excerpt of interview with Melkior Paron Tingang

Guardian of the memory

Tiong Ahoeng

East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 11’02”

Carl Bock wrote in “Headhunters of Borneo” (1881): ““The barbarous practice of head-hunting, as carried on by all the Dyaks tribes, not only in the independent territories, but also in some part of the tributary states, is part and parcel of their religious rites. Births and “ naming,’’ marriages and burials, not to mention less important events, cannot be properly celebrated unless the heads of a few enemies, more or less, have been secured to grace the festivities or solemnities. Head-hunting is consequently the most difficult feature in the relationship of the subject races to their white masters, and the most delicate problem which civilization has to solve in the future administration of the as yet independent tribes in the interior of Borneo. The Dutch have already done much by the double agency of their arms and their trade to remove this plague-spot from the character of the tribes more immediately under their control.”

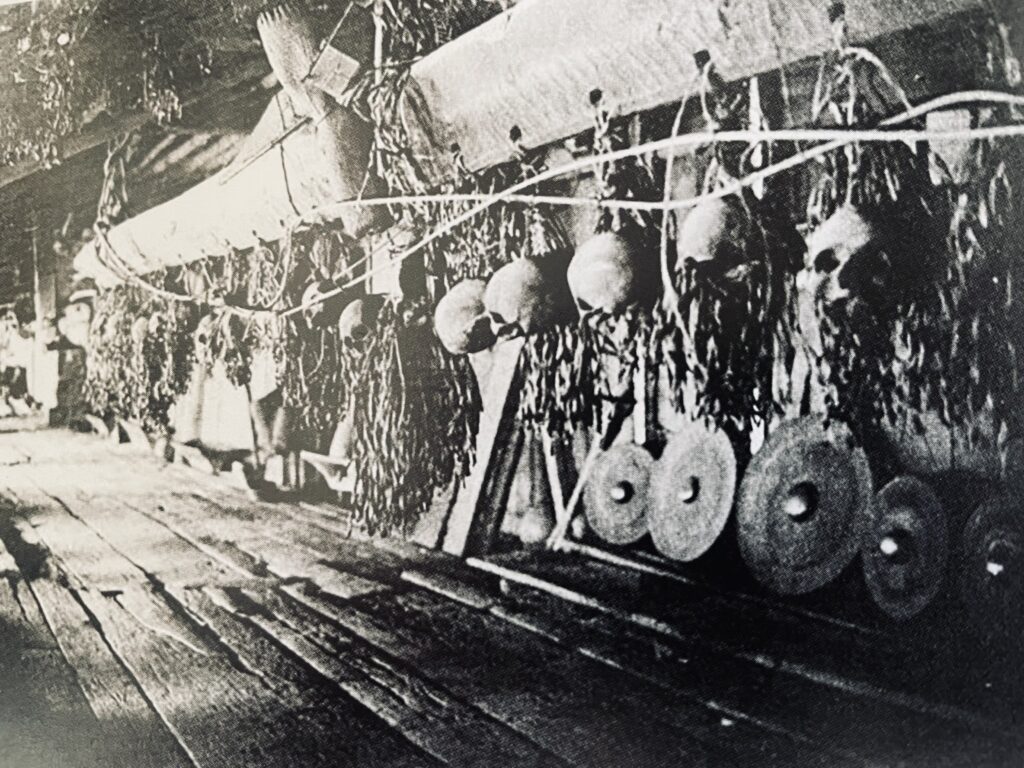

Skulls from headhunting raids have traditionally been displayed in longhouses. Some longhouses today still have heads hanging from the ceiling as relics of their glorious past. The most recent ones are Japanese heads taken in World War II.

Some collected an enemy warrior’s head to take home as a trophy or as proof of their victory. Others had to murder and bring the skull back to the village for permission to marry. Regardless of the motive, the practice of headhunting in Borneo has both intrigued and instilled fear in outsiders for generations. In longhouses one could see skulls still dangling from the roofs. Even today, the occasional rural community still looks after a head captured by their ancestors.

Headhunting was outlawed by the Dutch and the British on Borneo in the 19th century but continued sometimes there after.

Head hunting decreased over time, in part because of peace agreements in 1894 and 1924. In the 1940s, the Dutch made a major effort to crackdown on headhunting.

CAVES

In the Dayak world, caves can be used for habitats but they can also have some deeper spiritual and sacred meanings.

Dayak Tribes used to bury their relatives in caves.

Such ancient burial sites represent Dayak’s culture and way of living. Not only the cave holds tombs, but it can also store Dayak’s antiques.

The funerary material can include both pottery similar to Neolithic material elsewhere in Borneo and also materials associated with bronze artifacts. Some of the habitation sites may be pre-Neolithic on the evidence of multiple AMS dates between 4000 and 11750 B.P.; others are more recent.

Dayak warriors were headhunters who also carved the skulls of their victims to serve as trophies. Freshly decorated skulls were believed to have magical powers.

Caves

Undisclosed location

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 09’37”

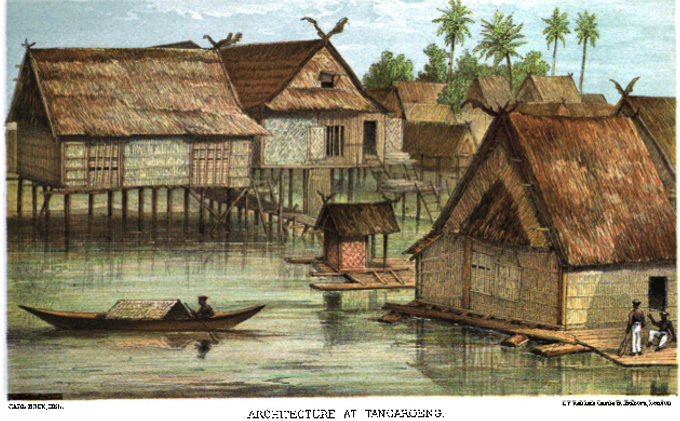

LONGHOUSES

The majority of Dayaks groups live communally along navigable rivers in protective raised village structures known as long houses.

Although some Dayaks still reside in longhouses that used to be served as a mean of protection against slave raiding and inter village conflict, during the headhunting days, the Dayak are not communalistic anymore. They have bilateral kinship, and the basic unit of ownership and social organization is the nuclear family.

Longhouse

Village of Muara Pahu

East Kalimantan. Indonesian Borneo.

4 K

2022

Reel Duration: 5’06”

Historically, these riverine peoples lived mostly in longhouse communities, seldom with more than a few hundred members, and traced their descent through both the male and female lines. The family was the basic unit, and children remained with their parents until married. Despite the lack of unity between groups closely related in language, custom, and marriage, a boy often sought his bride outside his own village and went to live in her community.

In contemporary society, however, many young Dayak men and women leave home before they are married, often to study or work in urban areas; many also pursue rural employment, usually at timber camps or on oil palm plantations.

Longhouses are large dwellings built by the Kenyah, Bahau, Modang, Lun Dayeh, and other peoples of the interior highlands of East Kalimantan and surrounding areas in central Borneo. Building a longhouse requires great expenditures of labor and materials as well as considerable skills in wood-working and engineering. Formerly found widely throughout East Kalimantan, longhouses are now built only in a few remote parts of the province; and only in the isolated Apo Kayan plateau are they still the predominant form of dwelling. (Longhouses of a modern type described below are still common in the Malaysian state of Sarawak in northwestern Borneo.) A longhouse (Kenyah umaq)1 is actually a row of contiguous family sections, each consisting of an enclosed apartment on one side of the house and an open veranda on the other. Both are covered by one roof, with a dividing wall between apartment and veranda under a ridge-pole. Extending outward from the front and rear of some sections are uncovered platforms used for drying rice, and some apartments have enclosed extensions at the rear to provide more interior space. Inside are sleeping compartments and places for cooking and eating, for storing household goods, and for various intimate social activities.

(SOURCE: Timothy C. Jessup. Consultant in Human Ecology. Rutgers U. )

https://folklife-media.si.edu/docs/festival/program-book-articles/FESTBK1991_14.pdf

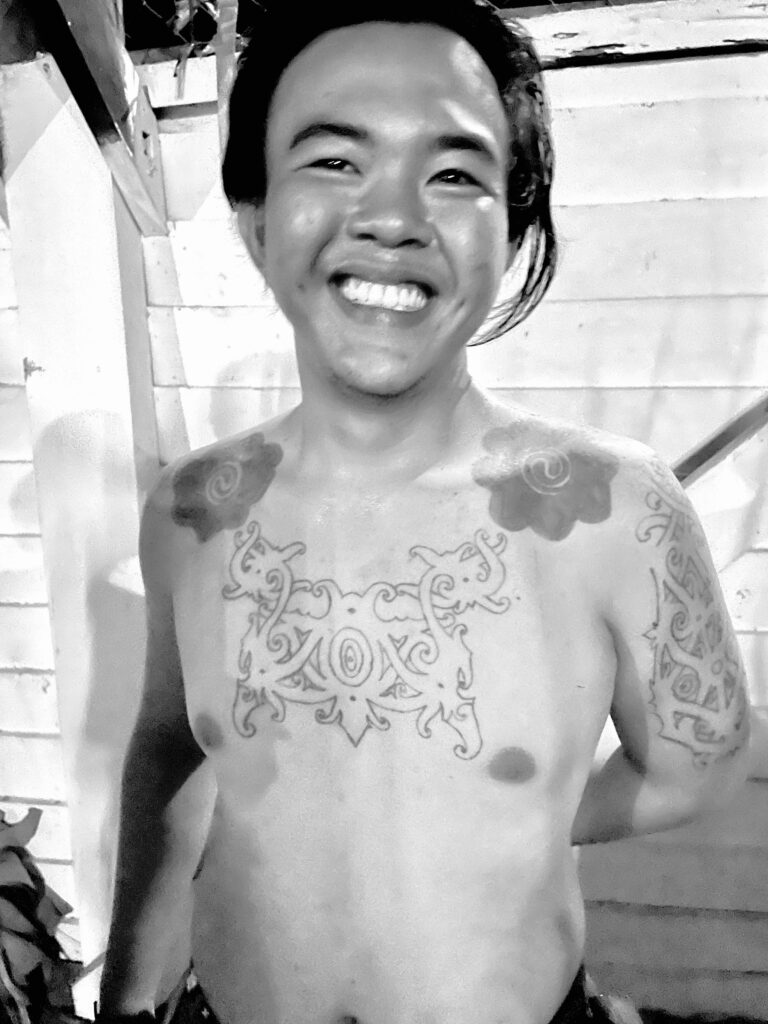

Dayak tattoos are known as “Tutang” and can be applied on the body for several reasons. Most notably, Dayak people believe that the black ink will turn gold after death. This alchemy is said to take place because of the memorial ceremony for the dead, and helps light the deceased person’s path to the after life.

THE FOREST

For countless generations, the Dayaks Borneo’s indigenous subsistence farmers and hunter-gatherers were animists and depended upon the forests by managing these as their primary source of livelihood. Under their stewardship, the forests were able to maintain the highest species diversity of any terrestrial ecosystem, supplying food, medicines, cash crops, and building materials.

Dayak Lands

(Ahoeng farming communities)

Tiong Ohang village

Upper Mahakam

East Kalimantan.

2022

4 K

Reel Duration: 4’03”

VILLAGES

Dayaks have traditionally lived in villages along Borneo’s complex river system, grown rice and other crops in shifting slash-and-burn plots, tended orchards and gardens that look like forests to outsiders, tapped rubber trees, and gathered forest products such as rattan, resins and gums. Dayaks grow special kinds of rice, sometimes named after ancestors and always adapted for their home territory.

To get around, the Dayaks have traditionally navigated the rivers of Borneo with dugout canoes that were propelled forward by ten standing punters. Today they mostly use motorized dugouts or long boats.

Dayak villages.

Muara Pahu/ Long Bagun

Middle Mahakam

4 K

2022

Reel Duration: 4’32”

RICE CULTIVATION

For rice cultivation, the Dayaks practice land clearing and crop rotation.

They cut down the trees, work the land, and when they feel the soil’s nutrients are starting to run out, they abandon their fields to become forests again, waiting to be cleared again.

This cultivation method created natural ecosystems with high biodiversity, rich in carbon stocks and low risk of soil erosion.

Rice planting.

Community of Liggang Melapeh

(Kutai Dayaks)

East Kalimantan.

2023

4 K

Reel Duration: 2’55”

Dayak religious beliefs

KAHARINGAN

The Dayak communities are today divided among several ethnicities, and most of their members have embraced major religions such as Christianity or Islam.

Some of them such as the Ngaju in Central Kalimantan still shared a belief system called Kaharingan (which still permeates their culture today). According to this belief, the world is populated by invisible spirits.

Kaharingan is a term in the Sangen (Old Dayak) language, built on the root haring. Haring means “to exist and grow” or “to live well”, a concept symbolized by the “Tree of life”, known

as “Batang Garing”.

Kaharingan is now a recognized religion since a few years.

It is now mainly organized by committees.

In East Kalimantan, Kaharingan is called Hudoq. It is more a celebration for planting rice, for water and good harvest.

HUDOQ

Huddoq

(after rice planting)

community of Liggang Melapeh and Geleo Baru)

East Kalimantan.

2023

4 K

Reel Duration: 4’19”

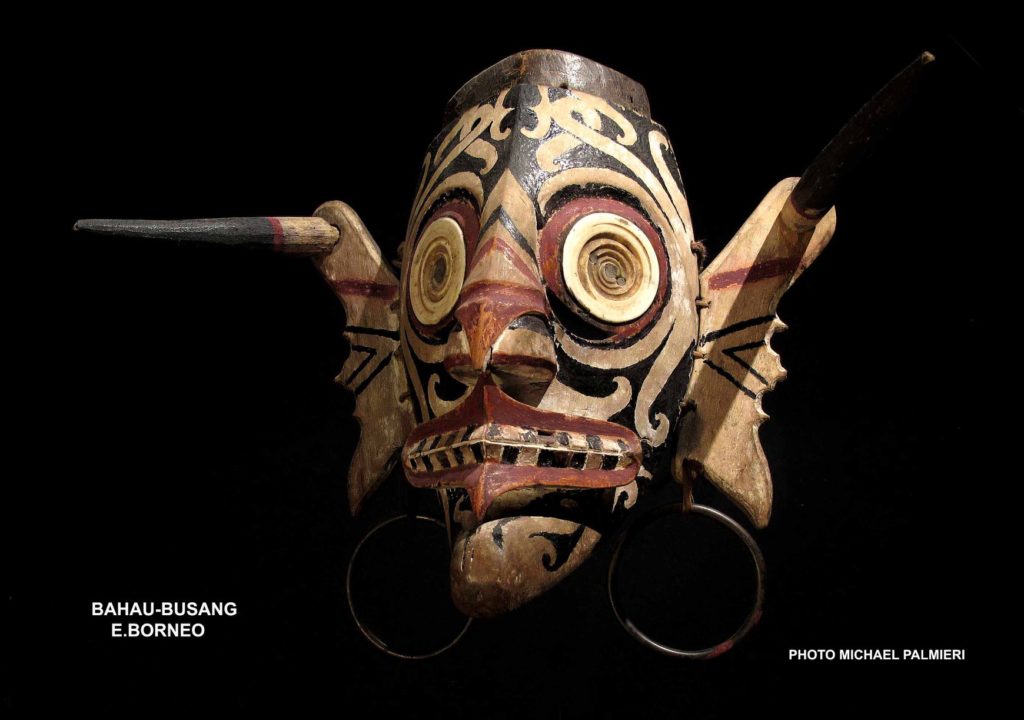

Hudoq is a manifestation of the spirit/god of Hunyang Tenangan, the rice-keeping god sent by the Lord of Apo Lagaan (Heaven) named Ine Aya’. The arrival of the god spirits to the earth is to answer the prayers of men who are doing Menugal, a process of notification to the ancestors and gods that the Dayak tribe will start to plant rice, corn and sugar cane in their fields.

To expect blessings from gods, it is not enough just by Menugal, the Dayak tribes have to prepare a Hudoq dance which is a hereditary inheritance in their families.

A way for the Dayaks to give thanks and receive blessings

UDOQ (modern)

Bahau Dayaks.

Tering Village

East Kalimantan.

2022

4K

Reel Duration:07’53”

UDOQ (traditional)

Kenyah Dayaks.

between the 19th and 20th century

Leiden University Library

16m/m

Reel Duration:06’33”

In addition to ceremonies connected with the fertility and protection of crops, hudoq masks were also enlisted by shaman

healers to treat certain illnesses that were thought to be caused by bad spirits. In these ‘curing’ rituals, shamans used the same sympathetic magic employed in the agricultural ceremonies. The grotesque and frightening masks were donned in an attempt to scare away the bad spirits that were generating ill-health.

Michael Palmieri. Bali. March 2022

Belian healing ceremony

In regard to religion, Dayaks tend to practice either Protestantism or Kaharingan, a form of indigenous religious practice blending animism and ancestor worship classified by the government as Hindu. Through its healing performances, Kaharingan serves to mold the scattered agricultural residences into a community, and it is at times of ritual that the Dayak peoples coalesce as a group.

Shamanic curing, or balian, is one of the core features of these ritual practices. Because illness is thought to result in a loss of the soul, the ritual healing practices are devoted to its spiritual and ceremonial retrieval. In general, religious practices focus on the body, and on the health of the body politic more broadly. Sickness results from giving offense to one of the many spirits inhabiting the earth and fields, usually from a failure to sacrifice to them. The goal of the balian is to call back the wayward soul and restore the health of the community through trance, dance, and possession. [Source: Library of Congress, 2006]

Belian Bewo ritual (night)

Tunjung Dayaks.

Kutai Regency East Kalimantan

2022

4 K

Reel Duration: 9’05”

Belian Bewo ritual 1 (day)

Tunjung Dayaks.

Kutai Regency East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 08’13”

Belian Bewo ritual 2 (day)

Tunjung Dayaks.

Kutai Regency East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 08’00”

excerpt of interview with Evi Ernes

Kutai Regency East Kalimantan

Tungjung Dayaks.

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 02’12”

Kuangkay

Funeral ceremonies are called “Kuangkay” and conversion to Christianity did not obliterate these practices. The invocations sung by the specialists will accompany the final journey of the souls in the world of the beyond. It is only on the 8th day, after the celebration of other rituals in the longhouse, that the participants plant the “blontang” pole, to which the buffalo will be tied for its sacrifice, on the 13th day, before the end of the “blontang” ritual. second funeral. On this occasion, the bones are dug up, cleaned and the skull is placed in a particular receptacle in the shape of a house. The “blontang” are metaphorical representations of the deceased, highlighting certain traits of their personality, their social status or their physical appearance. They are produced on the initiative of the relatives of the deceased, who bear the cost. They become prestigious effigies, placed in front of the longhouse.

excerpt of interview with Empu Gelollw (Dayak Benuaq carver)

Samarinda

East Kalimantan

2022

4 K

Reel Duration: 04’11”

In the following clip Empu Gelollw explain what is Kuangkay.

excerpt of interview with Empu Gelollw (Dayak Benuaq carver)

Samarinda

East Kalimantan

2022

4 K

Reel Duration: 04’51”

In this clip Empu is talking about initiation of being a Bintang Nyulir, an official title

passed down from generation to generation by a master carver of Blongtang (Dayak Benuaq statue) whose name is Bintang Nyulir/

THE OLD SNAKE RELIGION

Dayak “psycho-navigators” use visions and dreams to help them find their way in the forest. Dayak shaman practitioners of the “Old Snake religion” describe a hidden highland lake where enormous aging pythons enjoy dancing under the light of the full moon to honor the forest god Aping. Many Dayaks are Christians who have incorporated animists concepts onto their belief scheme. Missionaries went through the trouble of backpacking in paints and brushes to make hellfire scenes on the sides of longhouses. On the positive side missionaries have helped the Dayak clear landing strips which can be used for medical emergencies. [Source: “Ring of Fire” by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York.

CHRISTIANITY

In the 16th century the Portuguese introduced Catholicism to what is now Indonesia. In the 17th century the Dutch introduced Protestantism. Although some local people who worked with Europeans in the colonial administration converted to the religion, Christianity did not make much headway with the local population expect in a few areas like East Timor and the Spice islands.

From 1835 to 1925 the Rhenish Missionary Society (protestant) worked on the island of Borneo among the Dayak people. Progress was slow because the Dayaks held tenaciously to their traditional beliefs and practices, and also because of Muslim opposition. By 1925 there were only 5,400 Christians. From 1925-35 the Basel Mission took over but faced also many difficulties. The church became autonomous under the name Dayak Evangelical Church. It endured great hardships under the Japanese occupation. In 1950 the church adopted the name Kalimantan Evangelical Church, to express the fact that the entire island, where other tribes live besides the Dayaks, is the church’s mission field .

Source: https://www.oikoumene.org/member-churches/kalimantan-evangelical-church

Good Friday (Easter)

Ohang Dayaks.

Tiong Ohang

East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 03’16”

Easter Monday

Bahau Dayaks.

Long Pahangai

East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration:04’22”

Religion is perhaps the most important thing for an Indonesian. It is illegal not to have a religion and a person’s religion is stated in her/his ID card beside all the normal information that an ID card usually include: address, date of birth.

However, there are people who are called “ID card Muslims, Christians” etc. These are people who are not particularly religious as they do not observe their religious practices, but when asked they would say that she/he is a Muslim, Christian etc. according to their family’s belief and what is stated on their ID card. [Source: Canadian Centre for Intercultural Learning, intercultures.gc.ca )

Today the Dayak religion called Kaharingan (see above) is recognized as an”official” religion and is now authorized to be annotated on their ID cards.

https://patrickmorell.com/works/people/#kaharingan

This said, some of the indigenous communities of east Kalimantan, like the Punans still refuse to have an I.D card because of their non affiliation with any religion at all.

https://patrickmorell.com/in-production/#punan

LAND RIGHTS

The indigenous people of the Indonesian part of Borneo (Kalimantan), are experiencing increased marginalization as they are losing the rights to their land.

For many Aboriginal cultures, land means more than property– it encompasses culture, relationships, ecosystems, social systems, spirituality, and law. For many, land means the earth, the water, the air, and all that live within these ecosystems. As scholar Bonita Lawrence (Mi’kmaw, Indigenous studies at the University of Ontario Canada) points out, using historical examples: “to separate Indigenous peoples from their land” is to “preempt Indigenous sovereignty.”

Land and Aboriginal rights are inextricably linked.

Today, conflicts of interest between customary law communities and companies holding forest concessions for gold, between traditional communities and logging companies for wood and coal, have been inevitable.

In the 1980s, resistance began to emerge with the slogan “petak ayungku”, “my land”.

Peatlands and people are connected by a long history of cultural development. Humans have directly utilised peatlands for thousands of years, leading to differing and varying degrees of impact.

For centuries, some peatlands worldwide have been used in agriculture, both for grazing and for growing crops. Large areas of tropical peatlands have in recent years been cleared and drained for food crops and cash crops such as oil palm and other plantations. Many peatlands are exploited for timber or drained for plantation forestry. Peat is being extracted for industrial and domestic fuel, as well as for use in horticulture and gardening. Peatlands also play a key role in water storage and supply and flood control. •

Many indigenous cultures and local communities are dependent on the continued existence of peatlands, but peatlands also provide a wealth of valuable goods and services to industrial societies such as livelihood support, carbon storage, water regulation and biodiversity conservation.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hans-Joosten/publication/284054686_Peatlands_and_carbon/links/56b1c80508ae56d7b06b29e3/Peatlands-and-carbon.pdf

WALHI

WALHI, Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (Indonesian Forum for the Environment) was founded in 1980.

It is the largest and oldest environmental advocacy NGO in Indonesia.

WALHI unites more than 479 NGO’s and 156 individuals throughout Indonesia’s vast archipelago, with independent offices and grassroots constituencies located in 27 of the nation’s 31 provinces. Its newsletter is published in both English and the native language. WALHI works on a wide range of issues, including agrarian conflict over access to natural resources, indigenous rights and peasants, coastal and marine, and deforestation. WALHI also has several cross cutting issues such as climate change, women and disaster risk management.

https://www.foei.org/member-groups/indonesia/

Excerpt of interview with Uli Siaga Artan

Director at WALHI

Jakarta

2023

4 K

Reel Duration: 11’45”

Indigenous issues in Indonesia and land rights

Excerpt of interview with Uli Siaga Artan

Director at WALHI

Jakarta

2023

4k

Reel Duration: 8’30”

About Indonesian constitution and Human Rights

AMAN

AMAN stands for Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara, the Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago. AMAN is a representative organisation that consists of a Central Governing Body with 20 Regional/Provincial Chapters, 99 Local Chapters, 3 Wing Organizations representing Youth, Women and Lawyers, and 4 Autonomous Bodies. AMAN represents 15 million individuals from 2,230 indigenous communities across Indonesia.

AMAN’s mission is to empower, advocate for, and mobilize indigenous peoples of the Indonesian archipelago to protect our collective rights, and to preserve our cultures and environments for current and future generations.

In an era of challenges including poverty, climate change, and conflict, AMAN provides innovative solutions by utilizing indigenous values, knowledge, and solidarity to promote social justice, ecological sustainability and human welfare.

Excerpt of interview with

Dominikus Uyub

near Pontianak

West Kalimantan

4 K

2022

Reel Duration: 7’18”

Other resistance movements have emerged in the last few year such as the environmental group Walhi,

and from other educated Dayaks who decided to return to their native village, to advocate their rights like Emerensiana Claudia Sarita.

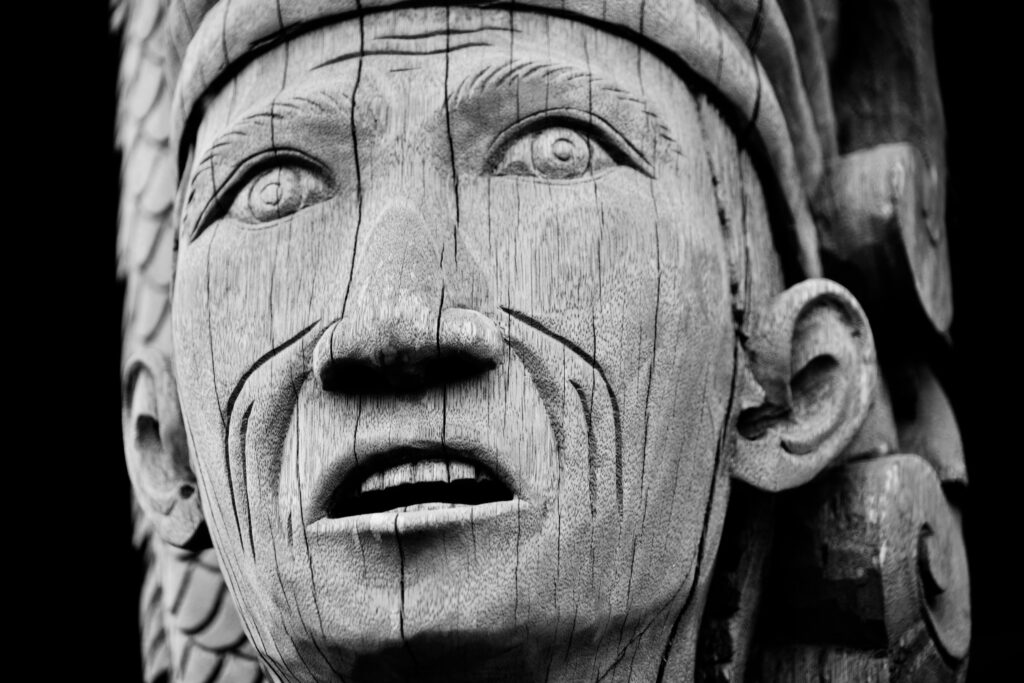

Dayak Sculptures. Hampatongs

In headhunting days, an hampatong was erected below the village for each head taken in a raid in order to appease the spirit of the victim and to prevent his or her retaliation against the living.

This practice has now disappeared with the eradication of headhunting.

Hampatongs can also represent named ancestors. They are erected in the vicinity of the longhouse and depict humans who have passed away.

They are the temporary “home” for the soul of the dead.

.

“My father name was” BAHRUDIN (Bruden)

He passed away on September 22nd 2021

My dad was a Dayak Benuaq carver.

He loved the arts and the sculptures so much.

And me too and my family too.

His statues are a memory of him.

My name is Rita.

I own a big lodge in Tanjun Isuy not far from the Mighty Mahakam river; a long house as vast as a small museum where my father’s collections of Benuaq Art, is.

Other carvings are represented with large posts in the form of human beings.

These usually represent important individuals or they refer to the significant members of the community (e.g., a hat that had been worn by an ancestor). These life-size statues can be male or female. They have been referred to as sapundu.

The Dayak call them “The Guardians of the spirit”

MANCONG

Mancong is small village of Benuaq dayak tribe around Jempang lake located in the West Kutai regency of East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo. People live an extremely simple life where much depends on the river water that surrounds their stilt village.

It has a traditional dayak longhouse called Lamin house.

Dayak Longhouse at the village of Mancong in East Kalimanta is a beautiful example of Benuaq Dayak people ceremonial hall which in the past was originally constructed to house up to 12 Dayak families. This Dayak Longhouse is famous for its many Patung or wood carved statue posts which are a sign of the number of buffalo’s killed at various traditional ceremonies.

In front of the longhouse are the patongs, of hampatongs, the wooden sculptures of people and spirits that define Dayak culture. Some are phantasy figures, but other have recognizable features, a hat, a moustache, a knife, clearly modeled on a once existing person. A great collection, which wouldn’t be out of place in any anthropological museum. And which is even more impressive in its original environment.

Mancong

Dayak Benuaq

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 11’03”

DAYAKS between Traditions , Modernity and Reality

Dayak men traditionally wore loincloths and had elaborate tattoos running up their shoulders. Sometimes they covered much of their body with tattoos. Women wore knee-length sarongs and went topless.

The women wear a short and scanty petticoat, reaching from the loins to the knees, and a pair of black bamboo stays, which are never removed except the wearer be enceinte. They have rings of brass or red bamboo about the loins, and sometimes ornaments on the arms; the hair is worn long; the ears of both sexes are pierced, and ear-rings of brass inserted occasionally; the teeth of the young people are sometimes filed to a point and discoloured, as they say that “Dogs have white teeth.”

The Memory of a People

Couple originally from the Apo Kayan region

Kenhya

Datha Bilang

East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 06’34”

Couple eating betel nuts

Ohang Dayaks

Tiong Ohang

East Kalimantan

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 06’07”

Many Dayaks now wear Western clothes, watch television and ride around on motorbikes. Their traditional homes sometimes have satellite dishes. Few live in longhouses anymore. Their traditionally dugouts have motors.

The Dayaks are regarded as one the most marginalized ethnic groups in Indonesia and Malaysia. They have been driven off their land by logging schemes, palm oil plantations, deforestation, settlers form other ethnic groups and transmigration schemes. They have been forced to move from their river villages to towns, often dominated by other ethnic groups. They claim they have been denied jobs, education and land and that settlers to their traditional lands are given preferences to these things. . The Dayaks are perceived by other ethnic groups as backward, stupid and lazy. They often occupy the lowest rungs of the economic ladder. The logging companies and palm oil estates prefer to use migrant laborers rather than Dayaks. Forced into the cities the Dayaks often find no work at all. To earn money, many Dayaks pan gold from the rivers in Borneo and tap rubber trees. Lucky ones get dangerous jobs in gold, tin and copper mines or at palm oil and coconut plantations.

Dayaks that remain in the forest have been hurt by drought, fires and soil erosion, The forests fires in the late 1990s were particularly devastating for them. Their villages were engulfed in flames and smoke, and trees and plants they depended on for food destroyed.

ANCIENT MYTHS and MODERN WARRIORS

THE PANGLIMA BURUNG

The Dayak Commander Of Birds

People believe that the other end of science is religion. And I added that the magic is in between. If one starts from the religion side, he will end up with science and vice versa. It does not matter which end you begin your journey, you must first pass through the test of magic. I have experienced magic, hope you will too.

The “Panglima Burung” or “Commander of Birds” is believed to be noble-minded Dayak leaders who possess magical powers and inhabit in the mountains of the interior of Borneo. There are the spiritual leaders, warlords, teachers, and elders.

The Dayak believed that these commanders have lived for hundreds of years and stay in the spiritual realm of interior Borneo. This commander of birds can be invisible, or take the shape of male or female. It may be the case that they were the spirits of late Dayak community leaders only to be conjured through a ritual for various purposes. However, there is another story that says that a “Panglima Burung” is the incarnation of Hornbill, a bird that is considered sacred and holy in Kalimantan.

THE RED ARMY AND THE PANGLIMA MANDAU

“I didn’t believe it myself,” says the schoolmaster, “but I saw it with my own eyes. There were just three soldiers in Salatiga, and when the Dayaks first arrived they fired into the air. But they were completely outnumbered, and they soon began shooting straight into them. There was one Dayak, he was 30 yards away. The soldier aimed the gun, it went ‘Bang- bang!’, but it didn’t hurt him. They were firing to kill, but none of the Dayaks got shot. I’d heard about it, but until then I never believed it. When they are in that state, when they are filled with the spirits, nothing can harm them.

It is said that “Panglima Burung” normally led a simple life. Although as leaders, they do not reside in the palace or luxurious buildings but they rather hide and meditate in the mountains and unite with the nature.

On the other hand, when the “Panglima Burung” is angry, they would descend from the mountain and gather their teams. They will then call a ritual known as the “Red Bowl”. This Red Bowl ritual is performed to gather Dayak warriors. During this Red Bowl ritual the warriors will carry out the famous war dance wilding the famous Dayak mandau swords as if hypnotized for war.

Aji Ahmad Ismail, also known as Panglima Mandau,

The mandau knife is a traditional weapon used by the Dayak people of Borneo. While mostly used as a jungle knife or for ceremonial purposes, it is sometimes associated with the tribal headhunting practices.⠀

The blade of the mandau is often forged from metal and inlaid brass. It has a single-edged blade with intricate engravings. It has an average length of 70 centimeters and known for its sharp cutting edge and flexibility. A high-quality mandau is called the mandau batu and it is said to be forged from meteorite stones. ⠀

⠀The mandau’s hilt is either made from animal horns or human bones. Sometimes it is carved in forms of anthropomorphic deities and other creatures. Dayak motifs are also carved on its wooden sheath, which is often wrapped in rattan, pig bristle, or human hair.

dapibus leo.