RAINFOREST

Environment

Forests play a key role in regulating the global climate seeing that more than one-third of the total Co2 reductions required to keep global warming below 2°C comes from them.

When mass deforestation happens, regional temperatures rise, which leads to drying and forest fires as seen in Brazil, California, Indonesia, Australia and the Congo Basin.

The Borneo rainforest is 130 million years old, making it one of the oldest rainforests in the world and 70 million years older than the Amazon rainforest.

Borneo is very rich in biodiversity compared to many other areas.

There are about 15,000 species of flowering plants with 3,000 species of trees, 221 species of mammals and 420 species of birds, many of them endemic to the forest.

Subject to mass deforestation, the remaining Borneo rainforest is one of the only remaining natural habitat for the endangered Bornean Orangutan.

It is also an important refuge for many endemic forest species, as the Asian Elephant, the Sumatran Rhinoceros, the Bornean Clouded Leopard, and the Dayak Fruit Ba

INTRODUCTION

about Borneo/ Kalimantan

with David Metcalf

Filmmaker (Long Saan documentary)

Bali 2022

4K

Reel Duration: 2′ 13″

DEFORESTATION

In the 1980s and 1990s Borneo underwent a remarkable transition. Its forests were leveled at a rate unparalleled in human history. Borneo’s rainforests went to industrialized countries like Japan and the United States in the form of garden furniture, paper pulp and chopsticks. Initially most of the timber was taken from the Malaysian part of the island in the northern states of Sabah and Sarawak. Later forests in Kalimantan, became the primary source for tropical timber. Today the forests of Borneo are but a shadow of those of legend.

The southern half of Borneo contains some of the richest and most unique ecosystems on the planet. But Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo , is also one of the most environmentally threatened places on Earth.

DEFORESTATION

Composite in various locations in Kalimantan related to deforestation

September/ October 2023

4K

Reel Duration: 4′ 45″

Deforestation in Borneo has taken place on an industrial scale since the 1960s.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the forests of Borneo were leveled at a rate unprecedented in human history, burned, logged and cleared, and commonly replaced with agriculture. The deforestation continued through the 2000s at a slower pace, alongside the expansion of palm oil plantations. Half of the annual global tropical timber procurement is from Borneo. Palm oil plantations are rapidly encroaching on the last remnants of primary rainforest. Much of the forest clearance is illegal.

Related Reels

Categories List

Palm Oil

Indonesia is the world’s largest producer of palm oil. In 2016, Indonesia produced 34.5 million tons of palm oil and exported 25.1 million tons. The total planted area of oil palm is estimated to be around 12 million hectares and is projected to reach 13 million hectares by 2022.

The Indonesian palm oil industry is dominated by large-scale private enterprises and smallholders, with government-schemes only playing a modest role.

Private enterprises produce roughly half of the palm oil and smallholders produce around 40%.

Major ecological threats from palm oil plantations are deforestation, biodiversity loss, and carbon emissions resulting from land use change and forest fires.

The disregard of indigenous rights by the palm oil production sector is also an area of high concern.

Palm Oil

around Pontianak. West Kalimantan

Drone by Dominque Clarisse.

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 4′ 47″

In this clip vast fields of oil palm trees neighbor a local palm oil company (part of a bigger consortium based in Pontaniak.)

This small company is managed by a Dayak (Bahau) who gave us the authorization to film.

PALM OIL FACTORY:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCszYCYopwE

Oil palm supplies 30% of world vegetable oil production. It is cheaper to produce than any other oils.

Plantation expansion is occurring throughout the tropics, predominantly in Indonesia, where forests with heterogeneous carbon stocks undergo high conversion rates.

(SOURCE:• Carbon emissions from forest conversion by Kalimantan oil palm plantations NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE Carlson, K. M., Curran, L. M., Asner, G. P., Pittman, A. M., Trigg, S. N., Adeney, J. M. 2013; 3 (3): 283-287

https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate1702

Oil palm plantations introduced earlier in Sumatra and West Kalimantan took the form of government enterprises using the ‘nucleus-plasma’ model. A large plantation, usually with facilities to produce crude palm oil, formed the ‘nucleus’, while smallholdings, usually of two hectares, constituted the surrounding ‘plasma’. In Central Kalimantan, however, oil palm only began entering in a big way after the International Monetary Fund introduced structural adjustment in the 1990s.

Structural adjustment was to be achieved through private investment, and large corporations were not interested in promoting smallholdings. So, despite national legislation making smallholder plots mandatory, throughout Central Kalimantan oil palm investment has taken the form almost exclusively of large plantations owned by conglomerates or business groups, often run as joint ventures with foreign investors. Privatisation of the sector has prevailed.

Source: Cetri Le Sud en Mouvement

https://www.cetri.be/Confronting-oil-palm-plantations?lang=fr

Since 2021, he government of Indonesia has made an effort to control the negative effects by issuing relevant policies. One of the policies is Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO)’s sustainability standards to which large-scale plantations and smallholders are obliged to adhere.

In 2022 the Indonesian government have also started to revoke many concessions to Palm oil large companies but many still remain especially in the North eastern part of the state among the Punan Batu tribes.

https://patrickmorell.com/in-production/

IMPACTS. HUMAN RIGHTS and PALM OIL PLANTATIONS

(Jakarta) – The Indonesian government has failed to protect the rights of Indigenous peoples who have lost their traditional forests and livelihoods to oil palm plantations in West Kalimantan and Jambi provinces. Loss of forest occurs on a massive scale and not only harms local Indigenous peoples but is also associated with global climate change.

The 89-page report, “‘When We Lost the Forest, We Lost Everything’: Oil Palm Plantations and Rights Violations in Indonesia,” examines how a patchwork of weak laws, exacerbated by poor government oversight, and the failure of oil palm plantation companies to fulfill their human rights responsibilities have adversely affected Indigenous peoples’ rights to their forests, livelihood, food, water, and culture in Bengkayang regency, West Kalimantan, and Sarolangun regency, Jambi. The report, based on interviews with over 100 people and extensive field research, highlights the distinct challenges Indigenous people, particularly women, face as a result.

West Kalimantan

“Indonesia’s Indigenous communities have suffered significant harm since losing their lush ancestral forests to oil palm plantations,” said Juliana Nnoko-Mewanu, researcher on women and land at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “The Indonesian government has created a system that facilitates the deprivation of Indigenous land rights.”

A complex web of domestic and international companies is involved in growing palm fruit, processing palm fruit into oil, manufacturing ingredients, and finally using these ingredients to produce consumer products sold around the globe – everything from biodiesel blends to frozen pizzas, chocolate and hazelnut spreads, cookies, and margarine, to the manufacturing of numerous lotions and creams, soaps, makeup, candles, and detergent. Given its ubiquity in consumer goods, every person globally has probably consumed palm oil in some form.

(Source: Human Rights Watch.)

https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/22/indonesia-indigenous-peoples-losing-their-forests

Mining and Villages in North East Kalimantan.

Much of the landscape of Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province has been transformed, its formerly vast forests razed for logging, monocrop agriculture and open-cast coal mining.

Industrial logging, rubber, oil palm, then coal. The snowballing effects of these extractive industries have divided local communities and destroyed livelihoods in parts of Indonesian Borneo, a new study finds.

“Communities who have had their land ‘grabbed’ by previous phases of industrial land use will experience the cumulative impacts of intensified extraction without necessarily deriving benefits,” lead author, Tessa Toumbourou of the University of Melbourne, told Mongabay.

Like a reverse evolution, some of the landscape of East Kalimantan province has already been transformed from the thriving ecology of primary forest to bare rock, passing through logging and monocrops, to open-cast coal mining.

Most of the region falls somewhere along that trajectory, with just fifteen percent still under intact primary forest.

(Source: Elizabeth Fitt. Montgabay Indonesia. 2022)

MINES

Composite in various locations in Kalimantan related to mining and other extractive industries on indigenous territories. (Punans)

2022/ 2023

4K

Reel Duration: 5′ 56″

Cocoa, an important cash crop many locals rely on for income, can’t withstand rapid cycles of scorched then saturated roots, or the pest problems that arrived with industrial oil palm.

Destruction of forest habitat has lead animals to seek food elsewhere – often eating smallholders’ crops instead of diminished wild foods—as well as reducing availability of forest products some locals relied on for income.

What comes around, goes around.

Cocoa prices are soaring to record levels. What it means for consumers and why ‘the worst is still yet to come’

The world is facing the largest cocoa supply deficit in more than 60 years and consumers could start to see the effect at the end of this year or early 2025, Joules said. The International Cocoa Organization has forecast a supply deficit of 374,000 tons for the 2023-24 season, a 405% increase from a deficit of 74,000 tons in the previous season.

Source: CNBC

https://www.cnbc.com/2024/03/26/cocoa-prices-are-soaring-to-record-levels-what-it-means-for-consumers.html

Environment and People. The Punan People (North Kalimantan)

The Punan are a nomadic indigenous community in the central and northern area of Borneo, both in Indonesian Kalimantan and Malaysian Sarawak and Sabah. As hunter-gatherers, the tribes rely on the forest as a source for food, medicine, water and all socio-cultural aspects of their life.

In the 1900s, the Dutch Indies colonial government started to organize the Punan to settle in permanent villages outside the forest, helping the colonial authorities to monitor and control the tribes. After decolonization in the 1970s, the Indonesian New Order government continued this approach through a project called population resettlement, organizing and registering the permanent villages of indigenous people to manage their developmental programs. The remaining indigenous communities were transferred from the interior forest to a new settlement located nearby the town. This approach left the forest empty and more open to exploitation and concessions.

Without education and having no control over their ancestral land, the Punan lived in the margins of society. The concessions of logging, mining and palm oil plantations exploited their forest and transformed their lifestyle to adapt into modern life. The Punan started to gain access to basic education in the 1970s when Catholic missions established schools in Malinau. Most of the students became village leaders and actively managed their villages. In 2005, they started to organize the community and created a network with local NGOs to conduct participatory mapping.

Many of the changes and developments that have taken place in the past few years have had, of course, ecological consequences, but they have also brought many new opportunities. For example, chances for employment have increased to some degree. Even if wages, according to Punan, are still very meagre, a few of them have nonetheless worked sporadically in road-building projects or as unskilled, low-paid labor in the logging industry. Proximity to timber camps has also given some households an opportunity to sell various products, such as fruit, meat, fish, and handicrafts. The arrival of a growing number of powerful outsiders, such as timber, mining, and plantation companies, have contributed to increased competition for land, but it has also created new opportunities. Claiming compensation for land that will be exploited or for farmland or fruit orchards that have been damaged is a new potential source of cash income. Although these claims are reasonable, they may nonetheless be used strategically by opening up a swidden or by planting perennial crops in areas that may become the next target for exploitation and, therefore, a generator of compensation money.

Lars Kaskija. (Stuck at the bottom. 2007)

This “grabbing” of the land by big companies (whether they are mining. or palm oil plantations) is very prevalent in the northern part of Kalimantan among the Punan Malinau communities especailly with mining.

According of the photo of the sign (middle picture) it looks like the forest has been already sold to PT MHL an energy plantation project and forbids any activities on the land except for the company.

Except it did not received the consent of the village and communities who used it for their food supplies and nobody knows who sold it and let alone for how much.

PT Malinau Hijau Lestari has been identified as working on an energy plantation project (energy plantation forest — HTE) on natural forest whose status is an “Other Use Area “(APL) in North Kalimantan. Apart from the high risk of deforestation, this timber plantation permit risks triggering conflict due to unequal land ownership.

To strengthen their recognition at the national level, the Punan community submitted application for recognition and protection of their customary community and its forest to the National Government in Jakarta in 2018 through a social forestry scheme.

The Ministry has reviewed the document and conducted field verification. When all requirements and verification will be approved, the Punan Community should obtain national recognition and have stronger legality to protect and manage their customary area in a sustainable way.

In the meantimes the company PT MHL has already acquired the land, which limits its access to the local communities.

Today, entire Punan communities and villages are now reduced to get their food supplies in the town of Malinau with the very little money they ironically can scrape in daily jobs in logging or mining companies.

Wild Ourangutans

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus Pongo, orangutans were originally considered to be one species. From 1996, they were divided into two species: the Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus, with three subspecies) and the Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii). A third species, the Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), was identified definitively in 2017. The orangutans are the only surviving species of the subfamily Ponginae, which diverged genetically from the other hominids (gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans) between 19.3 and 15.7 million years ago.

All three orangutan species are critically endangered.

Both the Bornean and Sumatran orangutans are typically tree-dwelling primates, however the Bornean species demonstrate much higher levels of ground travel than the Sumatran species—likely due to the absence of ground predators in the forest.

The Sumatran orangutan is often hunted by the Sumatran tiger.

The northwest Bornean orangutan is the most threatened subspecies. Its habitat has been seriously affected by logging and hunting, and a mere 1,500 individuals or so remain. Many habitat patches in the area are small and fragmented.

“Pepe” 2 Bornean Ourangutan

(P. pygmaeus)

Kutai National Forest

East Kalimantan

4K

Reel duration: 5’21”

Orangutans have an enormous arm span. A male may stretch his arms some 7 feet from fingertip to fingertip—a reach considerably longer than his standing height of about 5 feet. When orangutans do stand, their hands nearly touch the ground.

Orangutans’ arms are well suited to their lifestyle because they spend much of their time (some 90 percent) in the trees of their tropical rain forest home.

COAL on the MAHAKAM River

The Sultanate of Kutai Kartanegara ruled over most of the Mahakam River basin from its establishment in 1300 AD. Then came waves of disruption in the form of the Dutch, independence, and trans-migration. There is still a Sultan at the palace in Tenggarong – but nowadays on the Mahakam, coal is king.

For over a hundred years, the mighty Mahakam river, the third longest river in Indonesia and its surrounding ecosystems have been concessioned off to the extractive industry. Different parts of the Mahakam River in Kalimantan have been mapped, monetized and assigned different extractive purposes: logging, mining, industry, settlement, and many others. From 2009 to 2013, the Mahakam watershed lost 128 thousand of hectares of its natural forest due to wood extraction, mining, and wide scale plantations.

Every day, rafts carrying logs from pristine forests travel along the Mahakam towards processing plants while lines of barges transport timber and coal so it can be shipped to other parts of the country, Asia and Europe. These activities can be traced back to colonial days and have grown massively and systematically since Indonesia’s independence. Alongside the gas and mining industry, logging activities became the main income course under the authoritarian Suharto regime and his cronies from 1965 to 1998.

For more on the Mahakam please go to:

https://patrickmorell.com/works/nature/#mahakam

Logging (along with coal mining) is still the major industry up-river. The trees are usually felled some distance from the river, and brought by truck down rough forestry tracks to the river. There is no road to the mills in Samarinda, hundreds of kilometres downstream, so the logs are transported down the river.

Coal on the Mahakam 1

East Kalimantan. Indonesian Borneo/

2022/2023

4K

Reel Duration: 06’22”

Coal on the Mahakam 2

East Kalimantan. Indonesian Borneo/

2022/2023

4K

Reel Duration: 03’44”

There ís a lot of traffic on the Mahakam which is still, despite construction of lots of roads, a major highway into ‘The Interior’. And a lot of that traffic consists of coal barges.

Huge floating steel trays, each one hauled behind a large tugboat. Full barges, low in the water, heading downstream, and empty ones returning back upstream to be refilled.

The mining companies truck the coal to the river, where it gets crushed, stockpiled, and then loaded onto the barges.

These barges are big. Upriver (upstream of the Mahakam Lakes) they can ‘only’ manage a load of 5000 tonnes, but the downstream barges may carry 7-8,000 tonnes of coal.

The content of each barge gets loaded onto ocean-going freighters – near the river mouth, at offshore transfer stations, or at the port down here in Balikpapan. Some even gets towed across the Java Sea to Surabaya for local (Indonesian) use, but most is exported – primarily to China, India, Japan and Korea.

Coal on the Mahakam 3

East Kalimantan. Indonesian Borneo/

2022/2023

4K

Reel Duration: 06’11”

The river flows through Samarinda City, a trading port since the 1700s, which grew hand in hand with the extractive industry. Samarinda’s local administration has allocated more than 70 percent of the municipalities’ land for mining. The deforestation and soil erosion first from the logging industry and now from the coal industry’s digging of the soil, have caused substantial erosion and sedimentation of the river, leading to a dramatic increase in flooding. From November 2008 to June 2020, floods inundated almost every corner of the city, covering the main roads and interrupting economic activities, including public transportation and markets which consist mainly of women vendors. About 50,000 people have been affected by five to six major floods every year.

Coal mining is affecting families’ livelihoods and health, as flooding increases food prices and destroys houses, placing a heavier burden on women’s economic and domestic work. Mining has also displaced agriculture-dependent families from their lands and led to the death of children drowning in abandoned coal pits, of which there are more than 200 in the area.

ENERGY IN INDONESIA

Despite the country’s efforts to convert to more sustainable sources of energy, petroleum remains the backbone of energy provision in Indonesia, a country populated by 240 million people. Not only is the burning of fossil fuels a source of CO2 emissions, its exploration and exploitation are capital-intensive, a challenge for the country, and exposes communities and ecosystems to the risk of accidents like the Balikpapan oil spill in March 2018 to occur.

Pertamina produces about 800,000 to 1 million barrels of crude oil daily, leaving a 200-400,000 barrels gap to be imported. The spill in Balikpapan, the cost of which has been estimated in a decrease in oil supply of 200,000 barrels a day, is causing the gap to widen even further.

The worst cases of oil spills happened even with leading oil companies in the world, suggesting that even best industry practices aren’t a guarantee that incidents won’t occur.

Workers.

PT Pertamina refinery.

Balikpapan. East Kalimantan.

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 6’26”

Oil & Gas plant. Twilight

PT Pertamina refinery.

Balikpapan. East Kalimantan.

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 2’18”

JAKARTA

Jakarta is one of the world’s most overpopulated cities. Its greater metropolitan area is home to more than 30 million residents.

The sprawling megapolis sinks about six centimeters a year due to the excessive extraction of groundwater for its residents, according to a 2021 study by Indonesia’s Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology. This makes it one of the fastest sinking cities on Earth.

The phenomenon has been exacerbated by the rising Java Sea due to climate change.

A quarter of the capital’s area will be completely submerged by 2050 if urgent measures aren’t taken, the National Research and Innovation Agency said.

Researchers also believe water supplies may dry up for many in Jakarta and wider Java if Indonesia does not relieve pressure on resources.

“Jakarta and Java Island are heading towards a clean water crisis. We projected the crisis might happen in 2050,” earth scientist Andreas said, blaming rapid population and industrial growth.

“When the population explodes, the poor sanitation will get worse, pollutants will contaminate the rivers and shallow groundwater, rendering them unusable,” he added.

Pollution from Jakarta’s traffic-choked roads and the absence of a rubbish collection system – forcing many to burn their trash – has also produced air quality that at times rivals New Delhi and Beijing.

Time lapses. Jakarta by night

Java.

Indonesia

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 4’30”

Traffic. Jakarta by day

Java

Indonesia

2022

4K

Reel Duration: 7’00”

The city’s streets are so clogged that it is estimated congestion costs the economy €4.3 billion a year.

With more than 17,000 islands, Indonesia is the largest archipelagic nation on earth. But 56 per cent of its population and most of its economy are concentrated in Jakarta and the wider Java Island, which is home to more than half of the country’s 270 million people.

By comparison, East Kalimantan province – where the new capital Nusantara (an old Javanese term meaning ‘archipelago’) is being built – has fewer than four million people.

Another reason for the capital relocation cited by the government is disaster mitigation.

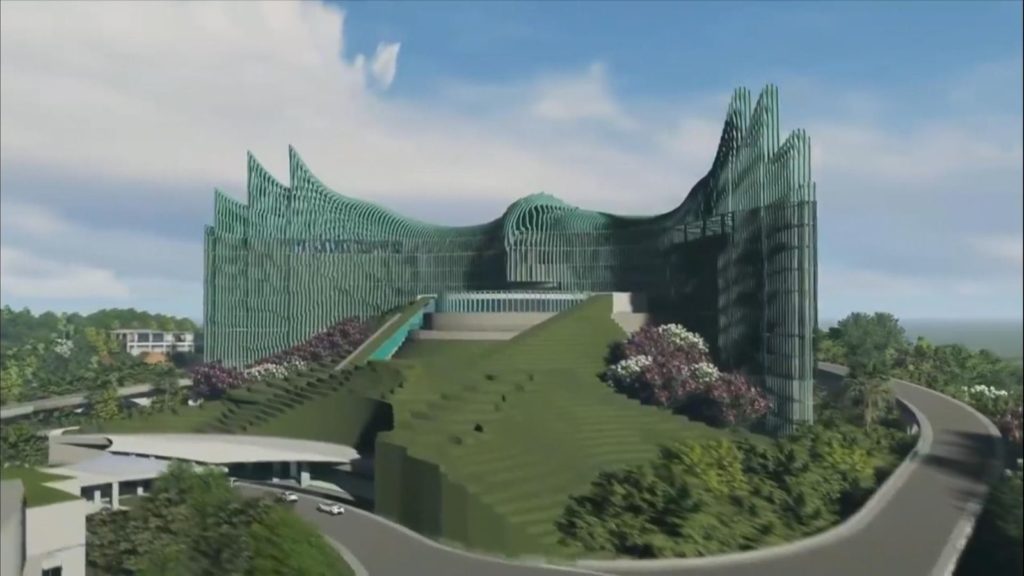

NUSANTARA

Located in eastern Borneo—the world’s third-largest island—Nusantara is set to replace the sinking and polluted Jakarta as Indonesia’s political center by late 2024. The relocation to the 2,560-square-kilometre (990-square-mile) area follows capital moves by Brazil to Brasilia—considered an urban utopia failure—and Myanmar to the ghost town of Naypyidaw.

Drastic changes to the land’s topography and the man-made disasters that could follow “will be severe and far more difficult to mitigate compared to natural disasters”, said UJI ARTA SIAGAN from the Indonesian organization WALHI.

WALHI is the largest and oldest environmental advocacy NGO in Indonesia.

Indonesia also has one of the world’s highest rates of deforestation linked to mining, farming and logging, and is accused of allowing firms to operate in Borneo with little oversight.

The government, however, says it wants to spread economic development—long centred on densely populated Java—around the vast archipelago nation, and to move away from Jakarta before the city sinks due to excessive groundwater extraction.

‘Working with nature’

Indonesian President Joko Widodo has pitched a utopian vision of a “green” city four times the size of Jakarta where residents would commute on electric buses.

His city authority chief, Bambang Susantono, presented the initial plan to journalists in mid-December 2023. pledging carbon neutrality by 2045 in what he dubbed the world’s first-ever sustainable forest city.

Environmental groups warn of an ecological disaster but architect Sofian Sibarani says the new Indonesian capital Nusantara will rise out of the forest rather than replace it.

But the two-hour drive from Balikpapan city to the sweeping green expanse of Nusantara’s “Point Zero” reveals the scale of the new capital’s potential impact on a biodiverse area that is home to thousands of animal and plant species.

With construction well under way (2023) environmentalists warn building a metropolis will speed up deforestation in one of the world’s largest and oldest stretches of tropical rainforest, estimated to be more than 100 million years old.

“It’s going to be a massive ecological disaster,” Uli Arta Siagian, forest campaigner for environmental group Walhi, told AFP.

The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (WALHI) is the largest environmental movement organization in Indonesia. Since 1980 until now, WALHI has been actively promoting efforts to save and restore the environment in Indonesia. WALHI works to continue to encourage the recognition of the right to the environment and the protection and fulfillment of human rights as a form of State responsibility for the protection of the people’s sources of life.